I’ve had quite a few people ask why I am not selling my µCurrent through international distributors like I did last time. Well, that’s a good question, and I’ll answer that as well as breaking down the economics of selling your own hardware product, what price you should sell your product at, and the pros & cons of using distributors.

The reasons I am not selling the µCurrent through distributors (resellers) this time around are as follows:

1) I make a lot more profit selling it myself. And, if I’m honest, the idea of a distributor making more than I do per unit kind of bugs me. Even if it means more work for me.

2) I have spent many months and a lot of effort setting up an Australia Post commercial account, and a system that allows me to sell and distribute my product easily and cheaply. Primarily for the Kickstarter campaign, but I was also thinking for the future. To now not take full advantage of that would be silly.

3) The vast majority of sales for my µCurrent come from my large audience base and my own marketing, SEO, and word of mouth etc. Very few people who know nothing about it will stumble across it on a distributors site and decide to throw one in their shopping cart. It’s a fairly niche product.

4) Customers will ultimately get a cheaper unit.

5) I like selling my own stuff, I still get a warm fuzzy out of it.

#1 Speaks for itself. Frankly, whilst I do enjoy doing this kind of thing and it’s part of my hobby (I’ve been selling hobby electronics kits/products for more than 20 years now), I am ultimately doing this to make money. I have to eat and support a family, and this is my day job. So the more profit in my pocket the better. I have no vested interest in helping make the distributors more money than I do.

#2 This is a big deal. I’ve done all the hard work and now have a very optimised process for shipping. My µCurrents come to me tested and individually packed, all I have to do is operate the shopping cart and eParcel system, print the labels and customs form, slap the stickers on and drive to the shipping depot nearby. It’s easier than it sounds. It takes me less than 2 hours tops to process 100 units and drive to and from the depot. Heck, the post office will even come and collect them if I bother to arrange it.

Incidentally, it would take about the same time to pack and ship bulk units to the distributors. So the time saving question has been rendered fairly moot.

This is a lot different to when I was doing the testing/packing, and manual labeling and customs forms like I was before. Back then it made sense to use a distributor to save a lot of time.

Although I will admit that there is the hassle of returns and inquiries, but this isn’t large. I get many inquiries anyway even when people buy from distributors. It’s not 100% hassle free either way.

Is it worth is economically for me to spend the time on this? Well, do the math like I will later and see. Yes, on a per hourly basis it is well worth it. And remember, this is part of my day job.

#3 This is more particular to my case than most, but it’s a simple fact that a niche product like this will not do much “passing trade sales” on the distributors websites. Because a) it’s not particularly cheap, so not at that “impulse” level, and b) it’s a niche use product, it’s not for general everyday use. This equation may certainly change if I have a product that appeals to a general audience.

#4 To understand why customers may ultimately get a cheaper unit, you have to look at the math I’ll do shortly.

#5 is a freebie for me. Forget I said it.

In my particular case, the only major advantage that a distributor can offer, and that’s offer to customers, not me, is faster local shipping within their own country. And potentially less import tax issues etc, but that gets complicated.

And BTW, using distributors is not a zero hassle solution. Unless you chose the completely hands off method like say Club Jameco. They do absolutely everything and you take home say 5-10% of the net sales.

The Economics Of Pricing Hardware:

There is an often thrown around figure of 2.5 times for hardware products. This is the Cost Multiplier. And 2.5 is not bad number to work from as a baseline as you’ll see shortly. Generally you’d want a good reason to go below this number.

If something costs you $50 in true cost to manufacture, you’ll likely want to sell it for 2.5 times that, or $125. Why? Well, read on…

First of all, pricing your product. There are two ways to price your product.

The first is the Bottom Up method.

This is where you take your base manufacturing cost, and then build a multiplier on top of that to get the retail price. That is the Cost Multiplier 2.5x number we are talking about above, and it is a number you need to pick based on what gross margin (profit) you need to make per unit in order for you to live and make this a viable business worthy of your time and effort.

This method works well for niche products that have little or no competition, or something new that is not available anywhere else, people will pay what they have to pay to get it, up to a reasonable limit.

Also, technical people understand this, and accept that you need to make a certain fixed margin. Typically you’ll try and make sure this figure is just above the one-off parts cost of someone making it themselves (customers will do the math!). So most would rather buy it from you assembled and tested instead of dicking around making it themselves.

The second method is called Top Down pricing.

This is used when you want to introduce a competing product into an existing market, or you have done your research and you know people will only pay a certain amount.

Essentially, you price the product “at what people are willing to pay”. If your widget only costs $10 to manufacture, and you know they will pay $100 for it, then great, your gross margin (essentially your profit) is huge. And you’ll be able to sell it through even the most markupidy (that’s a word, really) of distributors. But if that same product costs you $80 to manufacture, then well, congratulations, you are likely going to be working for minimum wage, and oh, by the way, no distributor will touch you with a 10 foot pole. In the OSHW industry, where your customers are cluey, you can’t get away with huge markups.

But in either case, remember, your gross margin will change drastically depending upon whether you sell the unit yourself, or you use a distributor.

Distributors:

So what about the economics of distributors? Time for some simple math.

Assume your widget costs you $50 to manufacture, and this has to include all your costs including parts, assembly, testing, shipping, packaging, consumables, taxes, defective units (allow say 5%), missing shipments (allow a few %) etc etc.

Using either the Bottom Up or Top down pricing system, you have determined a retail price of $125 for the widget. That x2.5 rule of thumb in this case, you’ll see why this number is important in a minute.

If you sell it yourself, (assuming the customer pays exact shipping cost) then you make a gross margin profit of $75 per unit.

This is a gross margin percentage of 60% ((($125-$50)/$125)*100%)

Assuming you sell 1000 widgets a year, that’s $75K per year profit, not including other business overheads of course.

That’s pretty darn good! That’s a decent full time living wage, you could conceivably quit your job to sell your one widget.

Now, what if you use a distributor? Ok, well:

Any distributor will want at least a 60% markup.

It’s important to understand what markup actually means.

Markup is the retail price divided by what it costs the distributor to buy it, minus one. So:

Markup = (Retail/Cost)-1

Sounds simple enough, and it is, but here is the kicker – If you want them to retain the same retail price you had in mind (or you are already selling at, because you know, it looks bad if you sell it cheaper than the distributor), i.e. $125 in this example, then they will want to buy it from you for about $78 at best to make their 60% markup

(formula rearranged) Distributor Sell Price = Retail / (Markup + 1)

Or $125/(0.6+1)) = $78 in this case.

Ok, so if you sell it to the distributor for $78/unit, your gross margin has dropped from 60% to 36%!

Profit = Distributor Sell Price – Cost

That’s a profit drop from $75/unit to $28/unit! (a 63% drop)

You now only make $28K/year for that same 1000 units. Still ok as a side business, but not one you’d quit your job for.

Yet you still have to do all the management work getting the parts purchased, manufactured, tested, packed, shipped, ad chasing your distributors to pay your invoice.

And worst of all, the distributor earns more than you do for your product! ($47 for them, $28 for you).

And let’s not even talk about who pays for shipping to the distributor, and any import taxes etc.

So that’s the hard reality using that Cost Multipler 2.5X rule of thumb. Drop that to 2.0X and the numbers start to look dire:

$50 profit for you without a distributor (still good), or $12.50 profit through a distributor.

That’s now 12.5% of the retail price in your pocket, and you are still doing most of the work. At this point you might as well take one of the royalty agreements were the distributor produces the product and just gives you a cut. Otherwise you are likely working for minimum wage or less. That’s no way to run a business.

Do the math. If you distribute yourself, you get an extra $47 per unit. If you charged your time at say $100/hr, that gives you a whopping 30 minutes to pack and ship each unit. Worth it? – you decide – working for the man, or you having your own business earning $100/hour for shipping alone. All for one single $125 product selling in not very high volume per year.

Selling your own product also gives you the greatest ability to discount the unit, absorb and offer free shipping etc. Something those down the food chain can’t often do.

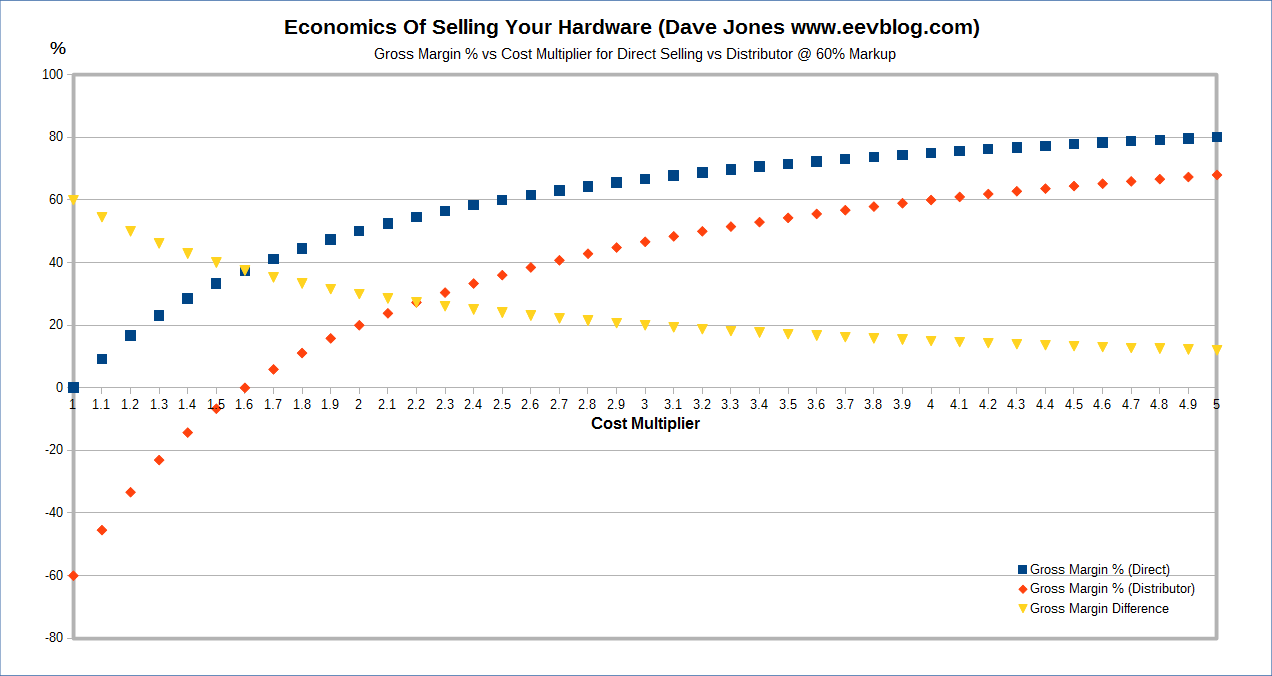

This graph of Gross Margin % vs Cost Multiplier for Direct Selling vs Distributor @ 60% Markup shows that you can’t even break even by using a typical distributor unless you have a 1.6X Price Multiplier.

This graph of Dollar Profit vs Cost Multiplier for Direct Selling vs Distributor @ 60% Markup shows (on the Difference line) that for you to earn half as the distributor per unit, you need to set a Price Multiplier of around that 2.3X – 2.5X mark. That is where that magic number comes from. Go below that multiplier and the distributor earns a vast amount more than you do!

Of course this is a just a war and fuzzy number, because, well, you are doing all the work getting this thing made. It makes sense for you to earn at least half of what the distributor/reseller does!

In Practice, The Value of Distributors

At this point there are many people who would be screaming at gaping holes in the above scenario, and well, you’d be right. But make no mistake, the above numbers are real if you fit the scenario.

The above is assuming that the distributor adds no value apart from taking shipping off your hands. And in reality that’s not the case, because they are a reseller who does much more.

A huge benefit is that they market your product to their established audience, and also in many cases (e.g. Sparkfun or Adafruit), their distributors as well. And that is why they need this big 60% markup, because they have distributors too, and so the math continues…

Distributors can have other advantages too, like handling returns and customer “where is my product?” complaints, and they take the cost risk on shipping if it goes missing. But ultimately, all failed goods will come out of your pocket, they usually won’t eat that. But thee are good benefits. And you only have to ship one bulk lot to them (they might buy say 50 as a trial then, then more depending upon sales), that’s a lot less hassle than shipping each unit yourself.

If you just want someone to take the burden of packing, mailing and distribution off your hands though, then what you want is a “fulfillment service”, “mailing house”, or the many names they go under. They will charge a much much smaller percentage, putting you back into the financial drivers seat. What you are buying with the big name distributors is their brand, their community, and their existing customer base.

You’ll note that in my situation above, I spent months organising and effectively setting up my own mailing house. So I get the benefit of discounted shipping rates like the big mailing houses, and a minimised workload that allows me to maximise my profit per unit. Not everyone will want to this, so there is great value in using fulfillment services for this.

So the real value with distributors/resellers is in the extra sales they bring over just having your own shop. Because they have the big ready audience you are looking for! What figure do they need to bring in to make it worthwhile going with them?, well, we can do the math on that too:

Assuming the original 2.5X scenario ($75-$28=$47/unit difference) and that you think you could sell 1000 units yourself. How many more sales would the distributor have to add on top of that for it to be worthwhile?

You are forgoing $75K profit, as you’d now make $28 per unit instead of $75, so that comes out to 2678 sales. So the distributor has to sell almost 2.7 times the volume you could on your own for you to earn the same $75K profit.

That’s not a bad figure, and any of the major distributor should be able to add that value fairly easily for a general purpose product. But the equation changes the more niche and the more expensive your product gets (#3 in my original list of reasons above).

And likewise, the equation could be drastically in the favor of of using reseller/distributor by even a 1000-1. If you don’t have a name for yourself, don’t think you can get your product mentioned on high profile blogs or whatever for exposure, then the choice is obvious, you go with the distributor with a huge ready sales and distribution channel.

If you want a bit of exposure that your own website won’t get, but don’t want (or can’t afford) a distributor or reseller to take a big margin, then you might want to use something like Tindie.

Conclusion

Don’t get me wrong, I’m not saying what to use either way for your own product, or that selling direct yourself is the best method. Even I may go back to using a big name distributor for more general appeal products in the future, as their customer base can be compelling, indeed, it may be your only or best option. Heck, the likes of Sparkfun have hundreds of distributors around the world, so if each one of those stocks 10 units, there is a thousand or two sales right there.

There are also countless other pros and cons and nuances and scenarios I haven’t touched on, and every situation is going to be unique. But at least I’ve hopefully presented some food for thought here and some basic numbers on how it all works. I hope you found it useful.

And ultimately, what I’d love to see most of all, is more people making full time livings producing useful hardware. Whether you anonymously sell countless different widgets you’ve designed though distributors, or blaze your own trail and make a name for yourself and distribute yourself, more power to you.

EEVblog No Script, No Fear, All Opinion

EEVblog No Script, No Fear, All Opinion